Each year on February 14, many people celebrate Valentine’s Day with cards, flowers, and tender expressions of romantic love and mutual affection. And there is nothing wrong with that. The experience of romantic love is a gift to be celebrated, and the mutually supportive love of a committed couple is a blessing to be cherished. But the traditional story of ‘Saint Valentine’ calls us to yet another kind of love.

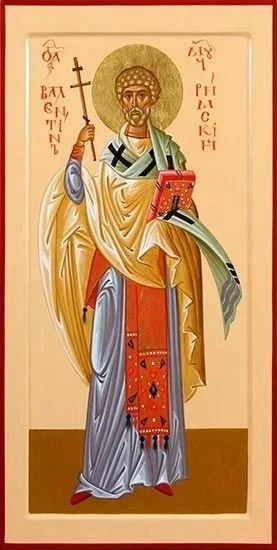

Traditions surrounding Valentine place him in third-century Rome during the reign of Emperor Claudius II. The details are layered with legend and there are a few different early traditions, but the most common tradition (perhaps a particularly popular combination of traditions) has remained more or less consistent since the earliest versions: Valentine was a Christian leader (usually described as a ‘priest’ or ‘bishop’) who ministered to believers living under an Empire that demanded—even if only symbolically and nominally—the acknowledgment of Caesar as divine and the Empire as that to which one owes one’s ultimate loyalty. Thus, the world in which Valentine found himself was one in which citizenship, social standing, and active civic participation, as well as all legal and many key economic transactions, were totally dependent on one’s unconditional acceptance and public affirmation of the absolute power of the Empire, acts that were inextricably intertwined with ritual acts of devotion to the imperial cult of Caesar.

Valentine is remembered for providing aid to the poor and needy; providing a welcoming space for the homeless, the outcast, and the exiled; and protecting those being persecuted by the state because they would not worship the gods of the Empire, nor any political leader - Emperor or otherwise - who claimed to be a god. But the main thing that connects him to later and contemporary celebrations of Valentine’s Day is that he secretly married Christian couples who were not willing to violate their conscience or blaspheme their faith by participating in the idolatrous worship of an authoritarian state and its absolute leader. Because of this unjust and oppressive situation, the marriage of committed Christian couples had to take place secretly, without the recognition or validation by the state. And so, to perform such marriages was not merely a matter of duty and kindness on Valentine’s part; it was also a politically subversive and therefore dangerous act. It was a declaration that ultimate loyalty belongs to God alone, not to a Caesar claiming to be a god and not to an Empire claiming sacred authority for its absolute and abusive power, as well as its unjust and brutal treatment of those who had no choice but to disobey its laws, resist its authority, and refuse to participate in many of the required rituals of civic life.

For his resistance to unjust and idolatrous imperial laws, Valentine faced constant danger, risking almost certain imprisonment and death. Apprehension, incarceration, and execution were not distant possibilities—they were ever-present dangers. Indeed, tradition holds that around 269 CE, Valentine was caught, imprisoned, and put to death because of a faithfulness that unjust authorities considered seditious.

Centuries later, there developed a tradition in which before he was killed, the martyr sent a note of love and assurance to fellow Christians and signed it “from your Valentine.” And by the time of Geoffrey Chaucer, the feast day and the signature of this final letter had become associated with courtly romance and the pairing of lovers. Eventually, Christian memory intertwined with imagery drawn from Roman mythology, and the martyr’s witness was transformed into a celebration of affection between lovers.

But, again, beneath the roses, gifts, and sentimental pictures of a cherubic Cupid shooting lovers with magic arrows, there lies a different story of love, one in which - in distinction from romantic love, and in addition to the mutually supportive love between committed couples - love is the kind of true commitment that is ‘faithful unto death.’

A Passion for Justice

As all Disciples should know, along with deep Christian spirituality and true community, a passion for justice is one of the necessary marks of a healthy and growing church. Based on how we use the phrase today, I am not entirely sure we could indisputably say that Valentine had ‘a passion for justice.’ It might be more accurate to say that he had a passionate love for people in need: the poor, the marginalized, the excluded, the exiled, the persecuted, and those whose love for and commitment to each other needed the kind of blessing and authorization they could not receive from a state that would require them to blaspheme their faith and deny their conscience. In other words, Valentines had the kind of zealous love that, although not entirely unrelated to a prophetic passion for justice, might more undebatably be equated with a radically pastoral passion for people.

To be clear, because of its radicalness, this kind of pastoral passion for people was no more based on sentimental piety than on sentimental love. Rather, this was an intense passion for people that is a truly faithful love of God inseparable from an honest and steadfast love of neighbor - whether individuals, committed couples, or a community of faith, all of whom need the kind of direction, guidance, comfort, strength, courage, and resilience inspired by the type of servant-leadership that is both inspirational and compelling because of its authenticity in both word and deed. What we are talking about here is the kind of pastoral passion for people that, when necessary for the spiritual and physical well-being of one’s neighbor, one’s community, and, indeed, all children of God, resists all forms of oppression by an authoritarian state, disobeys the laws that require violation of one’s conscience, rejects the idolatrous claims to divine status by any leader or any form of political power, and always, in all situations and circumstances, responds in love to ‘the least of these’ - and does so despite the ever-present risk of imprisonment, torture, and death.

Again, perhaps Valentine did not fully represent what we today might, strictly speaking, consider to be a prophetic passion for justice. But his radically pastoral passion for people is what led him to his passionate opposition to, and faithful resistance to, what we today also faithfully oppose and resist, but today seek to institutionally transform, based on a prophetic passion for justice: the marginalization, dehumanization, oppression, impoverishment, persecution, violation, abuse, torture, and execution of any of God’s children, any of ‘the least of these,’ especially by a state that believes itself to be absolute, demands one’s ultimate loyalty, and claims divine sanction for its use and abuse of power.

So, even as many of us may participate in the rituals of exchanging cards , giving flowers, and special dinners that highlight the thrill of romance, and as many also rightly affirm and celebrate the deep love and mutual support provided to each other by committed couples, maybe we might also take a little time to carefully and prayerfully consider the ways in which we - as individuals, couples, groups, or communities - might live our lives and witness to our faith through a loving, faithful, and, when necessary, costly passion for people, for both their spiritual and physical well-being - indeed, the kind of passion that leads us to oppose and resist oppression and abuse of any kind, which is the radical kind of passion for people that motivates, and will always animate, any authentic passion for justice. This, I submit to all Disciples of Christ as disciples of Christ, is the most faithful way to honor this martyred saint, and thereby celebrate the full meaning of what Valentine’s Day is all about.